America has a tungsten problem

The US will need a lot more tungsten in the future. Where will it come from?

Ned O'Leary

The United States needs a better plan for tungsten. For many years, the US has relied on Chinese tungsten production, but that's an increasingly tenuous position. Relatively conservative growth projections in defense and semiconductors suggest an escalation in tungsten demand. But if fusion technologies materialize, the United States will simply not have sufficient tungsten.

About Tungsten

Tungsten is a metal with a unique mix of properties. It melts at a higher temperature than any other metal. It is very hard, extremely dense, and broadly inert. Unlike other refractory metals, tungsten conducts electricity and heat fairly well.

Tungsten's major applications include:

- Cutting and drilling tools. Tungsten carbide's extreme hardness and high heat tolerance make it a great material for drill bits; if you're boring through the earth for oil and gas, you're likely using tungsten carbide. This is the primary application for tungsten now; estimates suggest it's about 60% of total consumption.

- Munitions. Tungsten's high density and chemical inertness make it useful in armor piercing rounds and certain specialized explosives. It's an alternative in many cases to depleted uranium.

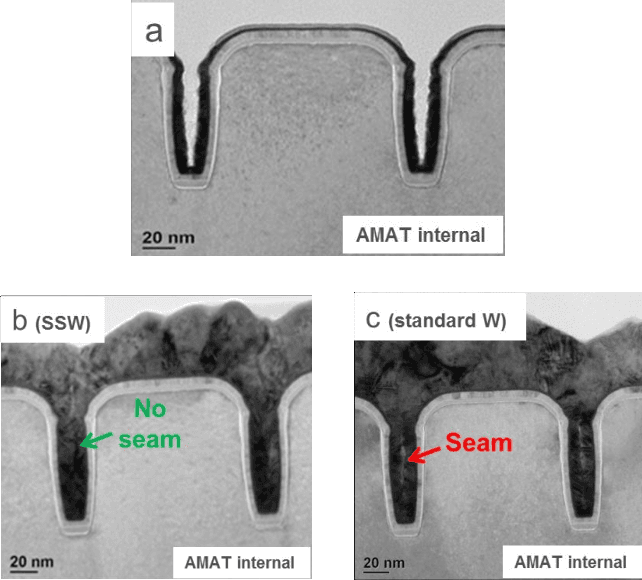

- Semiconductors. Tungsten's high melting point, inertness, adequate conductivity, and fluoride chemistry make it a useful metal for filling nanoscale connection gaps in semiconductors via chemical vapor deposition.

- Photovoltaic cells. Traditionally, photovoltaic cell manufacturing (i.e., making solar panels) used carbon steel wire to cut silicon wafers. Manufacturers increasingly use tungsten wire instead, because it allows them to get a much lower wire diameter, which in turn reduces the amount of silicon wasted with a given cut.

Tungsten carbide roller cone bits used in drilling for oil

Tungsten has an emerging application tied to the future of energy: it's an essential input for nuclear fusion reactors.

Tungsten is really good at resisting heat and erosion from neutron bombardment. It's a leading candidate for plasma-facing components and radiation shielding in fusion reactors. ITER has some good articles about why they use Tungsten, including this one about the extreme heat conditions that parts need to endure.

Tungsten is a weird and mostly forgotten element. It just doesn't command the same attention as rare earth metals. But it's really important for major industrial technologies!

Tungsten demand

In steady state, United States needs to import about 10,000 tons of tungsten each year. And American demand for tungsten might be going up. My handwaving guesstimate below hazards that the United States could need 15,000+ tons each year under somewhat moderate assumptions. If we allow ourselves to imagine fusion technology working, we can guess that the United States would have to find a way to match Chinese tungsten output.

Tungsten demand: conventional applications

If we refer back to tungsten's main applications, we should recognize that demand will likely increase. Let's engage in a thought experiment with a grotesquely simple model:

- Assume the amount of tungsten consumed in a given application varies proportionally with the market's overall size. Why not? Seems fine.

- Assign some hazy distributional assumptions to the different applications that consume tungsten. Let's say 60% of tungsten goes to cutting and drilling, 10% to munitions , 5% to semiconductors, 1% to photovoltaic applications, and then 24% to a bunch of other stuff. Let's round fusion to zero for now.

- Assign some hazy high/low guesses to different applications. Let's suppose that semiconductors and photovoltaic applications grow at a 15% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) and assume everything else grows slowly at a 5% CAGR.

We arrive at a hazy modeled guess of nearly doubled demand for tungsten in 10 years (+77%). These figures are all wrong, of course, but that doesn't mean they're not useful.

The important conclusions we should make here are all qualitative. Demand for tungsten in the United States is going up under relatively conservative assumptions.

CAGR | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | 2033 | 2034 | 2035 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutting and drilling | 5.0% | 60% | 63% | 66% | 69% | 73% | 77% | 80% | 84% | 89% | 93% | 98% |

| Munitions | 5.0% | 10% | 11% | 11% | 12% | 12% | 13% | 13% | 14% | 15% | 16% | 16% |

| Semiconductors | 15.0% | 5% | 6% | 7% | 8% | 9% | 10% | 12% | 13% | 15% | 18% | 20% |

| Photovoltaic | 15.0% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 4% |

| Other | 5.0% | 24% | 25% | 26% | 28% | 29% | 31% | 32% | 34% | 35% | 37% | 39% |

| TOTAL | 5.9% | 100% | 106% | 112% | 118% | 125% | 132% | 140% | 148% | 157% | 167% | 177% |

Tungsten demand: what about fusion?

I intentionally left out fusion above. What if it really happens? There are an awful lot of brilliant people working hard to make fusion happen. There's ITER, as I mentioned before, but there are also a bunch of commercial startups. It's not impossible that some of these organizations make real headway over the next decade.

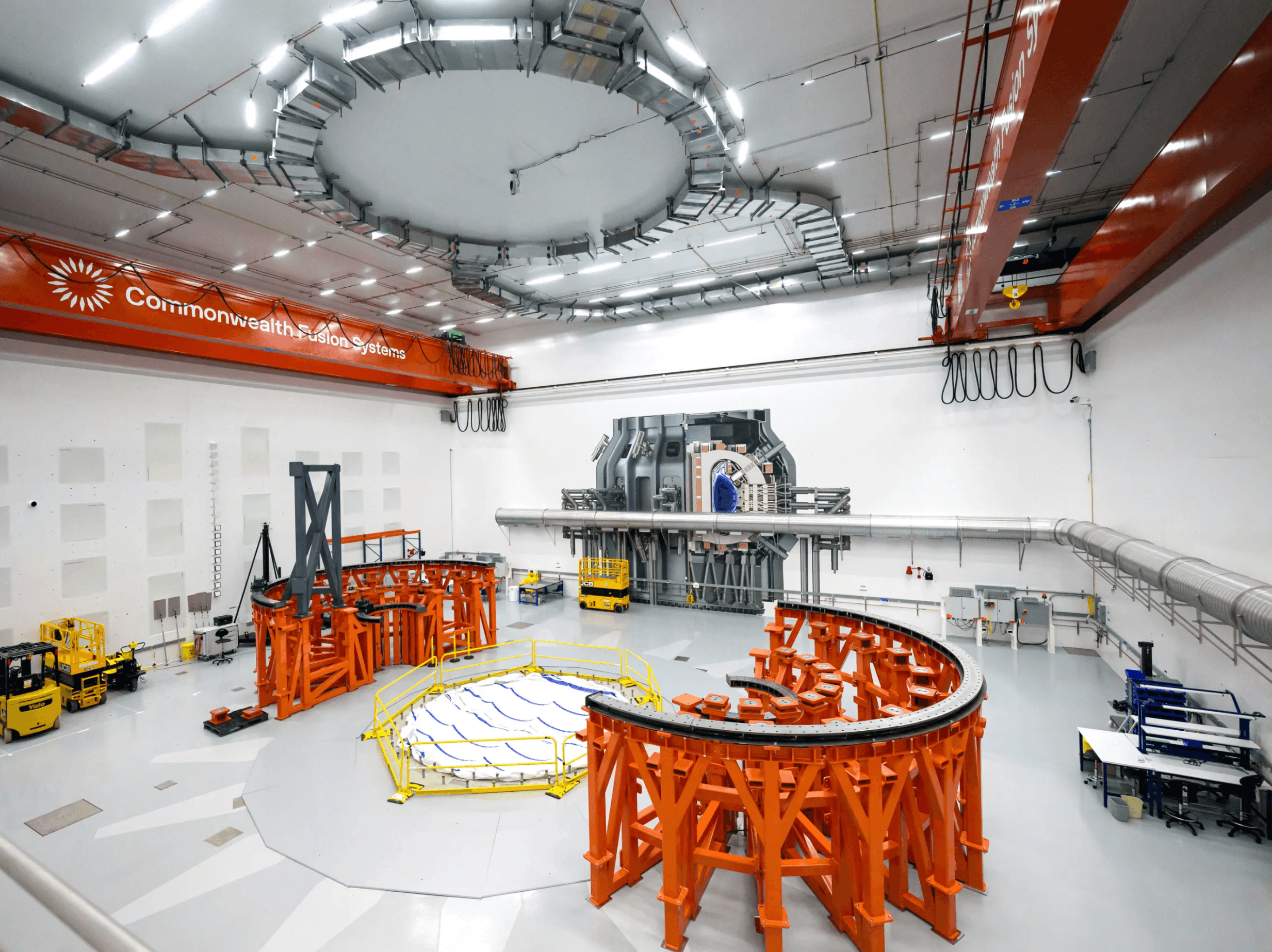

A lot of people smarter than I am have invested time and credibility in the promise of fusion on the horizon. For example, DeepMind partnered with CFS, Microsoft agreed to buy power from Helion Energy, and Helical Fusion arranged a power purchase agreement with a major Japanese supermarket. Even when you cut through the PR here, there's undoubtedly a kernel of real optimism.

An image from CFS's tokamak hall

I can't pretend to know what a fusion reactor's appetite for tungsten would look like. I genuinely don't know. I weakly suspect nobody knows.

I did find one paper out there. The paper suggests that a fusion reactor might consume 5,000 to 30,000 tons of tungsten over a 40-year lifespan. Let's just say that the answer is 10,000 tons over 40 years for simplicity. That's 250 tons per year per reactor.

What's a reasonable number of reactors? Here again, I can't pretend to know. I can only make a hamfisted gesture at the number of fission reactors that we already have. We know there are about 100 civil fission reactors in the United States. And then the US Navy has another 100 or so nuclear reactors, mostly on submarines.

In the absence of a good reason to believe otherwise, one might imagine the United States could have demand for 200 or so fusion reactors. This is again almost certainly an incorrect figure, but it's still useful for qualitative judgments.

For what it's worth, it seems the number here should actually be larger than the number of fission reactors. Fission is quite a lot more dangerous than fusion! We likely wouldn't need the same kind of tight regulation that applies to fission. A lot more people would likely build fusion reactors if the economics were there.

For what it's worth, it seems the number here should actually be larger than the number of fission reactors. Fission is quite a lot more dangerous than fusion! We likely wouldn't need the same kind of tight regulation that applies to fission. A lot more people would likely build fusion reactors if the economics were there.

If that's true, then fusion might account for the majority of future American tungsten demand. 200 reactors at 250 tons of tungsten per year totals 50,000 tons of tungsten per year.

If we combine this figure with our hazy baseline projection from before, we can loosely imagine tungsten demand in the United States approaching 60,000 to 70,000 tons per year.

I'll note as well that it's not strictly necessary for commercial scale fusion to start actually consuming tungsten. The mere prospect of imminent commercial fusion will impart demand pressure on tungsten supply. If or when commercial-scale fusion approaches, we will first see a scale-up of research projects. We'll also likely see stockpiling and speculation.

I'll note as well that it's not strictly necessary for commercial scale fusion to start actually consuming tungsten. The mere prospect of imminent commercial fusion will impart demand pressure on tungsten supply. If or when commercial-scale fusion approaches, we will first see a scale-up of research projects. We'll also likely see stockpiling and speculation.

Tungsten supply

Tungsten is an overwhelmingly Chinese industry; each year, China accounts for more than 80% of the world's ~80,000 tons of production. The next-largest producing countries in a given year are generally Vietnam, Russia, and North Korea -- and none of them are really major producers.

The United States has not produced any tungsten since 2015.

Global tungsten production, by year

Figures in metric tons

Source: USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries.

The United States has long relied on China for its tungsten supply. The United States has historically imported about 10,000 tons of tungsten each year. At that volume, where else could tungsten be coming from? No other country produces nearly enough!

Recent trade disputes have made American dependence on Chinese tungsten difficult to ignore. In response to tariffs, the Chinese government levied tight export controls on minerals including tungsten. To date, it seems that no US firms have received Chinese export licenses for tungsten. The controls functionally amount to a ban, even though no one wants to call it that.

The American-Chinese relationship lies somewhere between competitive and adversarial. I'll leave the characterization to the reader's individual politics. In either case, American reliance on Chinese tungsten (among other minerals) compromises its strategic position. The United States does not currently have an alternative supply of tungsten.

US tungsten imports for consumption, by year

Figures in metric tons

Source: USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries.

Supply can't just appear. Mines take many years and many millions of dollars to approach full productivity. Mines need to raise a lot of speculative capital, weave through a complex regulatory maze, recruit specialized labor, and ultimately ... get kind of lucky. Moreover, the mining business thrashes every few years from boom to bust and back again. You really can't count on the durable availability of private capital.

The natural solution for American interests would be to stimulate tungsten production elsewhere -- whether domestically or abroad. There just needs to be more non-Chinese tungsten.

This is underway, at least to some extent. The US Department of War has given some awards to American and Canadian firms that are developing tungsten mines. The Trump administration stepped in to push forward an American-Kazakh tungsten deal late last year.

But that's probably not sufficient. We need to engage seriously with the scale of the problem here. American demand for tungsten already exceeds non-Chinese supply by a pretty wide margin. We can observe this in market prices, which hit all-time highs in recent weeks. And demand is probably going up.

Wrapping up

As things stand, the United States faces a problem. The country doesn't have a secure, viable supply of tungsten for the future. The United States therefore risks its domestic semiconductor and munitions industries over the medium run.

But there's an even bigger strategic pinch lurking over the next decade. Bullish prognostications about nuclear fusion might turn out to be right. We might end up getting functional -- it not yet economical -- commercial fusion in the 2030s. If that's true, then demand for tungsten will rapidly outstrip supply. Prices will soar.

The obvious solution is to mine more tungsten. After all, it turns out tungsten actually isn't hard to find! It's all over the United States. In fact, it's pretty much all over the world.

One wonders:

- Why does China produce >80% of the world's tungsten?

- Why has there been zero domestic tungsten mining in the United States?

- What needs to change for domestic tungsten mining to return?

- What will it take to make sure tungsten supplies survive the next boom and bust mining investment cycles?